Look at those chompers | Michael Miller/Texas A&M AgriLife

Towards the end of August, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reported the first travel-related human case of New World screwworm in the United States. Identified in Maryland, the patient, who had recently traveled from El Salvador where the parasite is active, developed myiasis (larvae infesting a wound) but fully recovered after treatment. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the case via telediagnosis, while HHS spokesman Andrew G. Nixon reminded us that the public health risk remains “very low,” with no evidence of local transmission. And while that statement does provide some sort of hope, at least as far as humans are concerned, the rare infection is currently serving as a reminder of the parasite’s creeping threat to Texas’s wildlife and livestock.

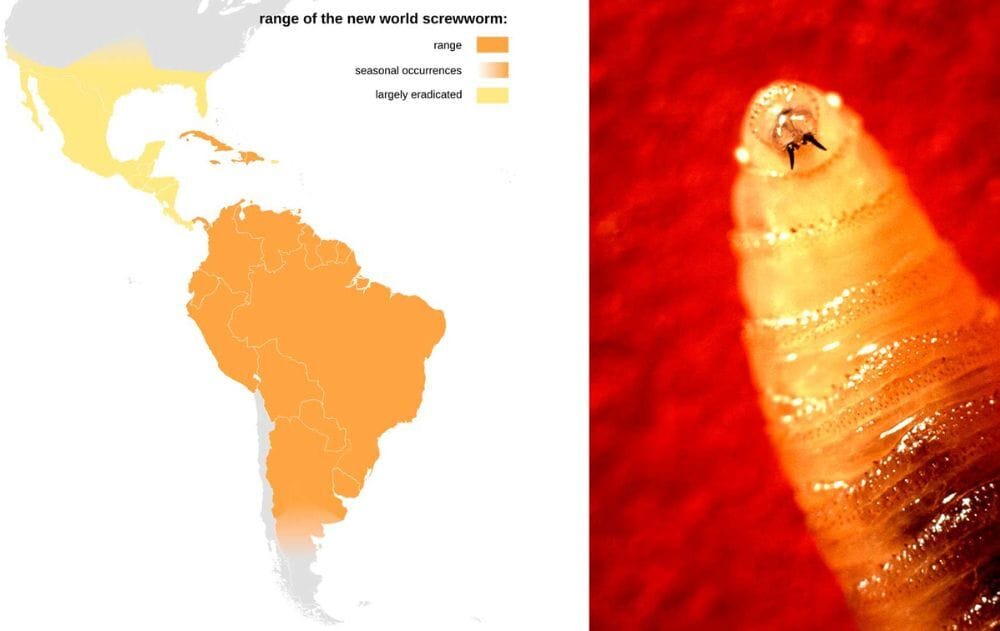

Just a few weeks later, a livestock infestation was confirmed in Nuevo León, Mexico—only 70 miles from the Texas border near Laredo. That case, detected just last weekend, marks the northernmost detection yet, following earlier 2025 cases in Chiapas and Oaxaca, Mexico. The New World screwworm (Cochliomyia hominivorax), a flesh-eating larval stage of a blowfly, has surged northward from Central America, escalating fears for Texas’s white-tailed deer, exotic game, and the state’s billion dollar livestock industry. No U.S. animal cases have been reported just yet, but the proximity has prompted Texas to halt Mexican cattle imports and tighten border controls.

NWS causes myiasis by laying up to 300 eggs per batch (3,000 over a female fly’s lifetime) in wounds or openings like nostrils or eyes. Within hours, larvae hatch, burrowing into living tissue with sharp mouth hooks, releasing toxins that enlarge wounds and can kill animals within weeks. While primarily affecting livestock like cattle, it also threatens wildlife, including Texas’s white-tailed deer.

“There’s a large concern, especially on the deer side, though it can be any mammal,” said J. Hunter Reed, Texas Parks & Wildlife Department veterinarian.

The USDA estimates a Texas outbreak could cost $1.8 billion in livestock losses alone, with broader economic impacts up to $10.6 billion. In light of the recent developments coinciding with hunting seasons across the state, hunters and landowners are urged to watch for the telltale signs of infection among deer and other species. These warning signs include irritated or depressed behavior, loss of appetite, head shaking or rotting flesh odor, visible maggots in wounds, lameness, nasal or ocular discharge and isolation.

Eradicated in the U.S. in 1966 via sterile insect technique, which includes releasing sterile male flies to disrupt reproduction, NWS is now a renewed focus. In June 2025, USDA Secretary Brooke Rollins announced a $8.5M–$750M sterile fly facility in Edinburg, Texas, set to produce 100 million flies weekly by early 2026. Other efforts include the deployment of 8,000+ traps across Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico, increased border patrols with “Tick Riders” and detection dogs, a $100 million investment in surveillance technology and Texas A&M’s AgriLife testing electron beam sterilization.

With over 1 million hunters in Texas, the community is critical to early detection. Texas officials are urging hunters and outdoor enthusiasts to report suspicious cases and to contact TPWD immediately if signs of NWS are spotted while afield.

“For hunters and also landowners, what we're saying is that if you manage to harvest an animal or if you see an animal on your property with clinical signs—that could be festering wounds, animals with lameness, discharge from the body or nose—they should call either their wildlife biologist or game warden,” Reed said. “That information will come to our wildlife health specialists and veterinarians on staff, and we can work to investigate the matter.”